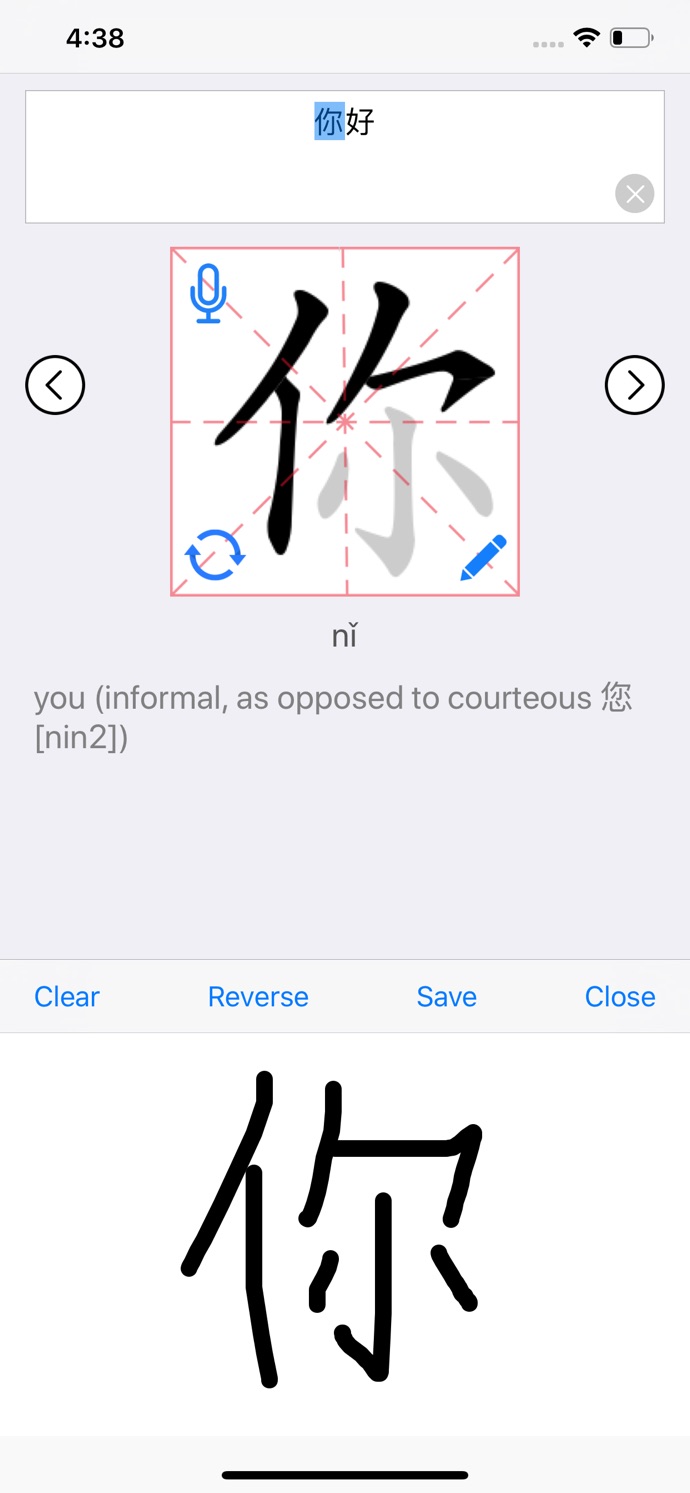

One of the most obvious examples is 中 (zhōng) where the 口 (kǒu) is written first and then the vertical stroke is written last.Ī few other examples are 半(bàn), 手(shǒu) and 串(chuàn). When there is a vertical stroke that cuts through many other strokes it is generally the finishing stroke. Vertical stroke cutting through comes last Similar to the Chinese stroke order rule of how the box or enclosure is closed at the bottom last, bottom “enclosures” also come last such as 远 (yuǎn), 脑 (nǎo) and 延 (yán). Some examples of this are 因 (yīn), 国 (guó), 目 (mù) and 园 (yuán). This means that the contents of the enclosure come before the last stroke of the ensclosure. Box is closed lastĪs we just saw the frame of a character is written first, however if there is a bottom horizontal stroke then this is always written last. The Framing strokes of characters such as characters that are enclosed by the 囗 (wéi) radical are drawn first, apart from the closing stroke (more about that in the next rule).īasically you want to write the outside of the stroke before you write the contents inside, here are a few examples: 间 (jiān), 回 (huí), 日 (rì), 月 (yuè). However, there are a few characters where this is less clear and you need to remember that the left sloping stroke must come before the right-downward stroke such as 父 (fù), 文 (wén). Here are some straight forward examples of this 人 (rén), 八, (bā), 六 (liù) where the characters can also be shown to follow the usual left to right rule. Left-sloping stroke before right-downward stroke The most simple example of this is 十 (shí) where the horizontal stroke is written before the vertical one, some other examples are 大 (dà) and 天 (tiān). Next up we have the rule that horizontal strokes come before vertical strokes. Horizontal strokes before vertical strokes Some examples are 你 (nǐ), 谢 (xiè), 做 (zuò), you should be able to see how these characters can be broken down into separate parts. When writing each component also remember that the top to bottom rule also applies. Many Chinese characters are made up of two or three components, so each of these should be finished before moving on to the next one. The second foundation rule we have for you is that characters should be written left to right. This rule also applies to more complicated characters that are “stacked” such as 茶 (chá). Think of some basic characters like 二 (èr), 工 (gōng) or 三 (sān) and you can clearly see the order these characters should be written in. Our first foundation rule is that most characters should be written from top to bottom.

However, with more complicated characters this can be confusing to figure out and there are also other rules which can apply so let’s have a look at eleven key rules to help you master Chinese stroke order! Top to bottom There are two general foundation rules which are: top to bottom and left to right. When it comes to Chinese stroke order there are some key rules that you can apply to make sure you’re doing it correctly. Stroke order really helps when it comes to distinguishing between similar characters like 末 (mò) and 未 (wèi). Instead you’re learning to recognise the character rather than learning to actually write the character from memory. If you’re just typing a character into a computer or phone using pinyin you’re not really learning the character in the same way as writing it out. Learning Chinese stroke order will also really help you memorise characters better. Knowing the correct order a character should be written makes it easier to break the character down into different components, such as identifying what the radical in a character is. Check out the two GIFs on the side to see how important the stroke order is even for a simple character like 文 (wén).Īnd it’s not just apps that will rely on stroke order to often recognise characters, many Chinese people do it too.Īnother reason learning stoke order is important is because it can really help you understand Chinese characters better.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)